| ||

| Must I live like Mother Teresa to deserve my life? |

|

| Or can KenKens also be part of a worthy life? |

This morning after I got up from bed, performed my morning ablutions, and breakfasted, I spent a half hour answering personal emails and perusing the local newspaper. I then spent most of the morning watching a “Great Courses” educational video called “The Joy of Mathematics,” which returned me, happily, to my high-school days of quadratic equations and geometry proofs. Then I took a half-hour nap. Then I had lunch while watching The Golf Channel. Two minutes ago I began this blog post.

This afternoon, after writing here for a bit, I plan to skim today’s New York Times online and download the Times’ crossword puzzle and KenKens, which I expect to finish in 30-45 minutes. Sometime this afternoon I may, if it’s not too hot, spend a half hour clipping the front hedge. Early this evening I will play two hours of tennis. After that, I’ll have dinner, then spend several hours in our tv room watching the Yankees play baseball, flipping back and forth between that and random sitcoms and other sports. During commercials, I’ll catch up on a back issue or two of Time magazine or The New Yorker. Before I go to sleep around midnight, I’ll spend an hour in bed reading an interesting book about the Civil War. At various times during this whole day, I’ll enjoy some easy conversation with my partner Gail and, if he calls, my son Alex.

My question as I turn out the light tonight will be this: Did I earn the right to live today?

I will not teach anyone to read today. I will not help the hungry or the sick or the homeless in any way. I will do nothing to improve the life of a single other human being today unless—and this is a stretch—this blog post itself serves some meaningful purpose for those of you reading it. I made not a single sacrifice of time or energy today to lessen the suffering or lighten the load of another human being.

So I ask again: Did I earn the right to live today?

The question itself suggests the privileged life I lead. Only a very small percentage of the world’s population can spend a day like the one I describe above. The rest of the world’s people work—and most work hard—to earn their existence. As one of the first of the baby-boomers, I fully retired this past spring. This means I no longer have to work to earn enough money to live; I no longer have to provide any service to the rest of humanity in order to earn my way. I can spend my days pretty much as I wish, limited only by the fact that I am not, by U.S. standards, exactly rich. (My annual income, thanks to Social Security and pensions, is about $50,000 per year—rich by world standards, but not by U.S. standards.)

Again, mine is a life of privilege. I will be awake for about 16 hours today, and, as you see, during that time every single thing I do will be an exercise in personal pleasure, self-edification, or (in the case of clipping the hedge) self-service.

This is, by almost any criteria, a selfish day. Should I then be ashamed of it, and therefore of myself? Did I deserve to live today? This blog post is my attempt to explore that not-so-easy question.

| |

| Was Albert Schweitzer's life more worthwhile than mine? |

Now, it is true that not all of my days are so purely self-serving. I do occasionally give some time and energy to others. I voluntarily help coach the local boys’ high school tennis team for a few hours per week. I teach classes about writing, free, about twenty or thirty times per year. During election years, I work for my candidates a few hours a week for a few months. I edit the resumes, letters, and other documents of my friends and former students, gratis, whenever they ask me. I donate about 5% of my income to good causes. Starting this fall, via the Internet, I’ll begin teaching Tanzanian medical students how to write better in English, so they can apply for grants and create public policy to help combat AIDS and tuberculosis in their country; I’ll be paid a little for this, but only a fraction of what I would normally charge for my time. I tip handsomely and hold the door open for others. I perform little kindnesses for my friends and, occasionally, strangers. I am not entirely selfish.

Yet I estimate that I spend less than 10% of my waking hours helping others or providing any services to the world. The other 90% of the time, I’m playing golf, say, or reading books, or watching tv, or doing crossword puzzles. Ninety percent of my time, in other words, is pretty much devoted to personal pleasure and self-improvement. I give maybe 10 hours a week, maximum, to acts of volunteerism and charity.

What is such a life worth? Should I be ashamed for giving so little of myself to others? Did I deserve to live today?

You might think that the very fact that I’m asking these questions suggests that I am, somehow, ashamed. I’m not, though. I’ll examine my feelings about this after I’ve done the NYT crossword and KenKens. I’ll be back in a half-hour or so.

___________________

I’m back. The Times crossword and the KenKens were easy today—a pleasant bit of exercise for an aging mind.

Did I earn the right to live today? Perhaps the crossword and the KenKens are a good place to start the discussion. It is pretty well accepted by most philosophers that improving the lot of mankind is a worthwhile thing to spend one’s time on. Well, I’m part of mankind. Doing the crossword puzzle and the KenKens is not just a diversion; it is, according to psychologists, a way to keep my mind supple and strong, and even, according to some studies, to help ward off dementia. By improving myself, I have, no doubt, improved the world.

Likewise, when I play tennis or golf (especially if I walk the golf course), I am keeping myself healthy—surely an important contribution to mankind, since I am part of mankind. My sports activities also lower my stress levels. Watching the Yankees engages me with the world, entertains me, and thereby relaxes me (when it doesn’t, in a perversely pleasant way, set my nerves on edge). Reading books and magazines makes me a better-informed citizen and stretches my mind.

|

| Is watching the Yankees on tv a waste of my life? |

All these things improve me. Therefore, they improve a small slice of mankind—the me-slice.

But they don’t improve the lives of anyone else. True, if I have in fact helped ward off dementia and if I stay healthier a bit longer, I have made my son’s future life no doubt a bit easier, since he won’t have to worry so much about caring for me later on. And keeping myself healthy and happy no doubt makes the world a better place than if I were unhealthy and unhappy; unhealthy and unhappy people raise our insurance rates and, in my experience, tend to make other people unhappy, as well. But all that is rather hypothetical. In my retirement, I find myself spending 90% of the time indulging . . . myself. This isn’t a bad thing, and it’s better than making myself unhappy, but is it enough? Does this earn me the right to live?

The question is, of course, loaded. What does “earn” mean in this context? I didn’t “earn” my existence in the first place. I simply found myself alive one day. Is it even relevant to ask if we’ve “earned” our life? I don’t know the answer to that—our cats certainly don’t seem to worry about “earning” their life—but it seems to me that, as self-aware creatures, we generally want to live a life “worth” something. And do we “earn” life only by doing good for others? I don’t think so. Socrates, for example, said that the unexamined life “is not worth living.” This blog post is an example of my examining my life, so is my life “worth” more because I’ve written it? I’m with Socrates: I strongly believe the answer to that is yes.

|

| Our cat Spot Junior never asked if he deserved his life. |

I believe, then, that making myself happy and healthy (and keeping myself awake to things) is a legitimate part of living a worthwhile life, not just because it does good for me, but because, since I’m part of humankind, it does good for humankind. And I believe that examining one’s life, as in this blog post, is a worthwhile way to spend a piece of one’s existence.

I also believe that consciously appreciating one’s existence is a worthwhile way to spend a part of one’s life. Relishing a good baseball game, basking in the beauty of great books or great art, swimming in glorious music, weeping over a powerful movie or even laughing over a particularly funny sitcom (Modern Family comes to mind) are worthy ways to spend one’s life, as long as one consciously appreciates them along the way. Good conversation and sex are also valuable.

In sum, I believe that all these activities—from 18 holes of golf to great sex—help me earn the right to live.

But is that enough? My conscience—and a few thousand years of moral philosophy—tells me no. They tell me that I have not earned the right to live unless I have done good for others. More importantly, philosophy aside, I feel that I need to do good for others in order to deserve my life.

This, then, raises two questions: What good works should I do? And, How much time should I give to good works?

The first question strikes me as rather easy to answer: Anything you do to improve another person’s life is worth doing. At first blush, it seems obvious that helping a boy improve his tennis game is less “worthwhile” than feeding the starving or helping end torture or teaching an adult to read. But what seems obvious isn’t necessarily true. Helping a young man learn a skill—even just a sports skill—is valuable in itself, and the pleasure, confidence, good health, competitive escape, and general satisfaction that come from a lifetime of playing decent tennis is, I can tell you first-hand, a worthy addition to that kid’s life. It will make him happier, and happiness, though not the same as bread to a starving child, is no small thing to give

So I make no distinctions: Anything you do to improve another person’s life is worth doing.

The second question, as I said, is harder: How much time should I give to good works—that is, to doing for others? Is ten hours a week enough? Is twenty? Should one devote all one’s free time to serving others? Jesus might say yes. (Interestingly, teaching seemed Jesus’ favorite form of giving, as it is for me. Of course, if you’re a Christian, you believe he gave more of himself than just his words and an occasional foot-washing.) Mother Teresa and Albert Schweitzer, it is said, gave virtually every waking moment of their lives to helping others.

|

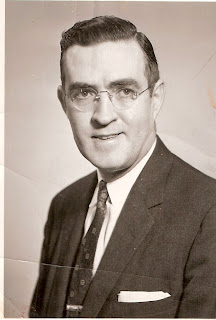

| My father, Terry Weathers, committed most of his life to helping others. |

For 50 years, my father worked 40 hours a week on his paying job and, on top of that, gave four or five hours a day to his volunteer work for things like Little League and, for most of the last thirty years of his life, his crusade to make public-school financing fairer for poor school districts; on the day he died, at age 83, he delivered Meals on Wheels that afternoon to old people in his community. My father exhausted himself in working for others. He enjoyed a ball game on tv and reading the daily newspapers, but he gave, I’d say, 80% of his time to others. Community service gave him great satisfaction.

But I find I can’t live up to my father’s legacy. I don’t even want to live up to it. My self demands more of my time. Oh, I shall continue to give my money to the ACLU, Doctors Without Borders, the YMCA, and Special Olympics—that’s easy. But I will dole out my time very sparingly: teaching a little tennis here and some writing there, working for my preferred political candidates when the time comes, and occasionally putting my thoughts on this blog, for whatever good that does anyone.

So did I deserve to live today? I don’t know. I do know that I did live today, and I actively appreciated that living. Tomorrow I may change my mind, but for now, this day will do.

|

| Was Jesus' life more worthwhile than the Laughing Buddha's? |

(This post was begun August 25, 2011 and finished October 27, 2011.)